And then …

Orcadians: Seven Impromptus

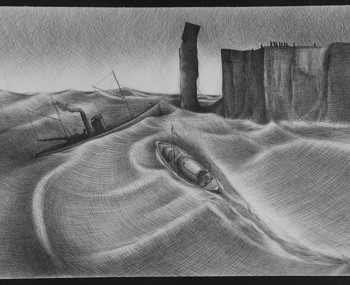

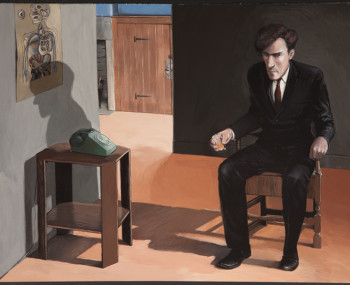

Brinkie’s Brae, 2009. Ink pen on paper. 210 x 297 mm

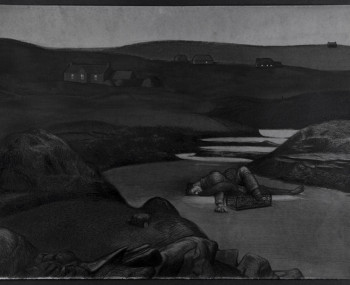

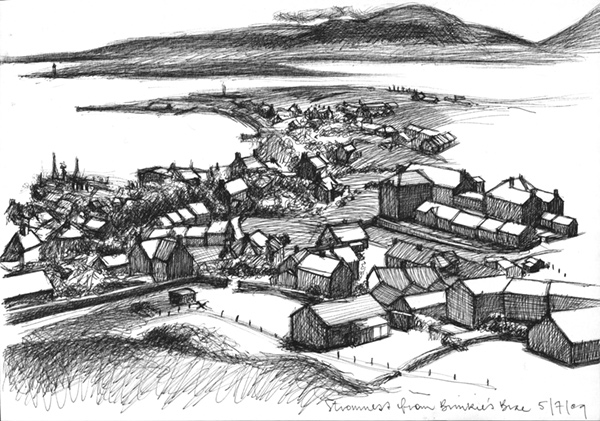

Lifeboatman, 2008. Ink pen on paper. 130 x 209 mm

I was first introduced to the writing of George Mackay Brown in the late 1980s while working as a bookseller in Edinburgh. I was particularly drawn to the poetry and short stories. His sentence construction, the sharpness and simplicity of his poetic vocabulary, enthralled me. He used a beautiful language, creating a sense of place with fable-like directness, cradling the words lovingly so that they fitted perfectly into the undulations of his landscapes, and describing the inhabitants of that place, Orkney, with an accuracy born of thorough acquaintance. The effect on me was immediate and profound, a permanent enchantment.

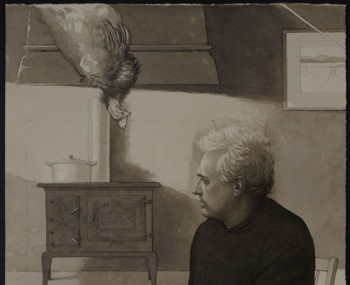

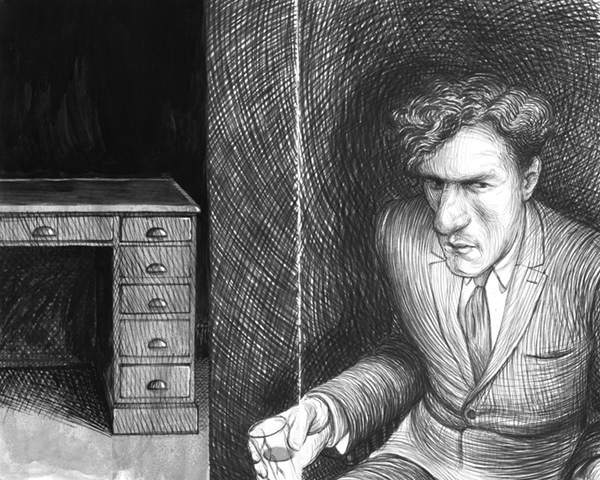

Doctor, 2010. Ink on paper. 209 x 260 mms

‘For the islands I sing’, the opening line from ‘Prologue’, the first poem in his first published collection The Storm And Other Poems (1954), immediately conjured up an image of the poet open-mouthed, crying out his song into the wild offshore island winds. I tasted and smelled the salt from the sea and heard the cry of gulls, all from a line of five words. The line encompassed for me the writer’s attachment to and love for the archipelago and its inhabitants. In other poems from The Storm – or later volumes of poetry – and in his short stories and novels I saw a wonderfully buoyant and, at the same time, dark imagery. It presented itself as a dimly realised drawing, lacking the finer detail, as if peered at through a veil. It was as if I could visualise the ‘feeling’ but not the physical drawing. Nor could I find the practical method by which to respond to the words. I felt unable to delineate what was in my mind’s eye. I let my desire to illustrate the work tumble around in my head, and for the most part kept it to myself.

At this stage of my creative development I felt unable to take the idea of illustrating George Mackay Brown’s work further, and, looking back, I am pleased that I was hesitant and waited. The writing needed not only a confident illustrator, which I was not, but one who could execute drawings that were fully formed or realised. I was not ready.

Starting at the beginning with The Storm, I fell upon the last poem in that collection: ‘Orcadians: Seven Impromptus’. This episodic, humorous, dark poem is a portrait of Orkney life and death, delving into the world of the characters that inhabit the landscape.

In 2005 John Murray published the magnificent Collected Poems of George Mackay Brown, edited by Archie Bevan and Brian Murray. Re-reading Brown’s complete verse oeuvre renewed my interest in his writing and impelled me to examine the idea of illustrating the work again. Starting at the beginning with The Storm, I fell upon the last poem in that collection: ‘Orcadians: Seven Impromptus’. This episodic, humorous, dark poem is a portrait of Orkney life and death, delving into the world of the characters that inhabit the landscape. The poem was one Brown considered worthy of dedication to his mentor and champion Edwin Muir. However, my reason for choosing to illustrate ‘Orcadians’ was a purely visual one. Each impromptu was a pictorial goldmine: I saw the attitudes of the characters and the treeless landscape, from foreground to horizon, from light to dark; I heard the lifeboatman ‘laughing at danger’ and ‘the yelp of a tinker’s dog’; I felt the farmers’ mistrust of the doctor ‘scattering barren wit’. Two years after the publication of the Collected Poems and with more than two decades of practice and experience behind me I felt, at last, ready.

Quite a few of the initial sketches were apprehensive and clumsy. Although I knew the islands a little from a previous visit, the drawings were that of a stranger, as if their depiction had been reliant on hearsay or rumour. I needed to be there to collect reference material and to work directly from the landscape. I hoped my drawings would display evidence of some knowledge of the lie of the land and recognition of those who peopled it. I did not want them to appear as if they had evolved through a stranger’s eyes, I wanted them to sit contentedly next to George Mackay Brown’s words – a kinship of words and pictures. I booked tickets and accommodation for the summer. However, I could not wait. A small rough for ‘Lifeboatman’, the first of the impromptus, was done early in 2008 and I was pleased with the results. The finished drawing in ink on paper was completed in June of that year. It pictured the lifeboat approaching, through seas rising and falling, the still chugging trawler run aground close to the headland, and the families of those on the trawler, along with the Old Man of Hoy, witnessing the drama.

The second drawing, for the ‘Saint’ impromptu, followed a couple of months later: simple Peter’s trusting face beneath the sea waters as he experienced his Pentecostal baptism, his eyes fixed beyond the viewers’ gaze, and his head haloed by fish. This was also in ink, as were the next two, ‘Fisherman’ and the character of Robbie from ‘Them at Isbister’. I had used that medium almost exclusively over the previous four or five years and was confident in its manipulation. For ‘Orcadians’ I took the process further by working on a larger scale, building the image up slowly in layers, applying the medium using pens, brushes and washes.

The next piece, ‘Cloud over Orphir’, didn’t quite fit within any of the impromptus but spoke more about atmosphere and was A1 in size, twice the dimensions of the drawings that had gone before. It also saw the introduction of colour in the series with the use of gouache, and was evidence of my presence in Orkney. ‘Cloud over Orphir’ was worked from a composite of three photographs of a monumental cloud that had all but obliterated the sky and diminished the surrounding settlements to mere flecks in the landscape, looking across to Orphir from Brinkie’s Brae above Stromness.

I spent a very pleasant afternoon at Hopedale, the Bevans’ house, chatting to Archie about George, the poet’s stint as a volunteer on the lifeboats, and the project. I was saddened by Archie’s death in February 2015 – I would very much like to have presented him with a finished copy of this book.

After much anticipation I arrived in Stromness to stay for a little under a month in June 2009, to begin the ‘field study’ I promised myself and to make contact again with Archie and Elizabeth Bevan. Archie Bevan was at the time George Mackay Brown’s literary executor and through his and Elizabeth’s daughter Anne – an old friend from my Edinburgh days – had given me verbal permission to illustrate the poem. I spent a very pleasant afternoon at Hopedale, the Bevans’ house, chatting to Archie about George, the poet’s stint as a volunteer on the lifeboats, and the project. I was saddened by Archie’s death in February 2015 – I would very much like to have presented him with a finished copy of this book.

That summer, Orkney was bathed in beautiful warmth and light. I spent a good deal of my three or so weeks on Brinkie’s Brae, scanning the rolling landscape. From the brae I had views in all directions: over the rooftops of Stromness and beyond, to Stenness and Orphir with glimpses of Scapa Flow; turning towards the hills of Hoy, their profiles vague in the summer haze; slowly shifting in the direction of the cliffs at Yesnaby in the distant west; and far to the north over Dounby and Evie on Mainland, then Rousay, Westray and the Atlantic.

I returned home encouraged, with sketches, photos and a store of memories to draw from. The more I immersed myself in the poem the more I saw in terms of imagery. Initially I envisaged one drawing per impromptu with ‘Cloud over Orphir’ representing a general visual motif, or introduction to the collection, but it had now become a more substantial recording of the narrative, with two or, in some cases, more drawings illustrating each impromptu. This was particularly true of ‘Chicken’ and ‘Them at Isbister’. ‘Chicken’ is the shortest and most rhythmic of the impromptus, but one with abundant illustrative possibilities. The tragic scene is depicted in slow motion and in real time, with the last two lines hinting at what will happen that evening, post-tragedy: the driver (is that Robbie from ‘Them at Isbister’?) announcing with glee the news of his bounty, and with that a future domestic scene can be imagined – chicken bubbling away on the hob, a warm evening of delicious road kill.

There’ll be hen for wur tea the night.’

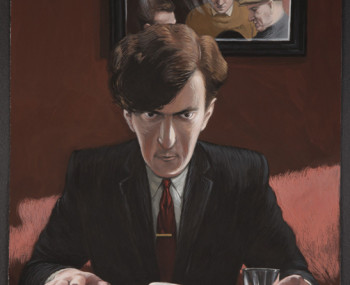

The characters of both Robbie and Janet in ‘Them at Isbister’ are so strong and so clearly drawn by the poet, their relationship so well understood, it would have been remiss of me not to offer each of them their own portrait.

The characters of both Robbie and Janet in ‘Them at Isbister’ are so strong and so clearly drawn by the poet, their relationship so well understood, it would have been remiss of me not to offer each of them their own portrait. But then I could not favour this and the ‘Chicken’ impromptu above the others, as they too deserved more than one illustration. Guthrie, from ‘Doctor’, is such a malevolent individual and the brief outline of his physical appearance at the very beginning of the impromptu so direct, a look of condescension on his face as he sneers at the ‘slow-spoken farmers of the parish’, that he cried out to be drawn more than once, and in more than one contextual situation. The only impromptu for which I could not readily visualise a second scenario was ‘Crofter’. I felt satisfied that the landscape of the croft at Biggings, the figures of Mansie, the excisemen and the cheating Walter o’ Grayland casting long shadows in the afternoon sun, described the narrative of the verse clearly and at one fell swoop.

Towards the end of 2014 I felt the series was near completion. I had recently finished another larger ink wash drawing, the same size as ‘Cloud over Orphir’ but in landscape format. It was a companion piece to an earlier version in ink for the ‘Fisherman’ impromptu. It is a dark, quiet and solemn depiction of the sea, the final resting-place of Jock Halcrow but, just as ‘Cloud over Orphir’ was first envisaged as a kind of visual motif for the whole series, an image that introduced the narrative of ‘Orcadians: Seven Impromptus’, this seascape could be seen as the series epilogue. It was however not the final piece to be completed. Over the last year I struggled with a number of images I had in mind for the ‘Chicken’ impromptu. Three remained half-done, like incomplete thoughts, as I worked on another. It was as if I were compelled to have my last word in visual terms and would not give in until it was spoken; or perhaps it was just that I could not let the project go. The last of the illustrations, a gouache of the driver of the old Ford turning back to see his bounty, the chicken, dead on the road and ready for the pot, was completed early in 2015.

I have now moved on, looked for a new project and considered the manner in which to present and express it. I cannot help, though, looking through the Collected Poems and hoping one line of another poem will drag me under the waves again, clinging to a fine brush and a pot of ink.

Text © Simon Manfield. Originally published in Orcadians: Seven Impromptus (2016), Kettillonia.

At the beginning of 2015 I made the last marks on the last illustration for the project, a companion piece for the Chicken impromptu. By this time author, publisher and friend James Robertson had offered to publish the collection of work alongside the poem as a limited edition hardbound book under the Kettillonia imprint, and with the kind permission of the Estate of George Mackay Brown it was made possible. On June 10th, 2016, along with the first showing of the completed series of drawings and paintings, the beautifully printed and bound edition of Orcadians: Seven Impromptus was launched at the Scottish Storytelling Centre in Edinburgh. The evening was a great success. I felt thrilled and overwhelmed to see the project come to fruition but the greatest emotion I felt was one of gratitude, to all who gave me encouragement, helping me to form what was a long fermenting concept into a tangible and very beautiful object. If you are interested in purchasing a copy of the book please visit the Kettillonia website.

Since the launch and first exhibition Orcadians: Seven Impromptus has been exhibited as part of the StAnza Poetry Festival in St Andrews in 2017 and at ArtsMill in Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire between September and October 2017.