A new body of work …

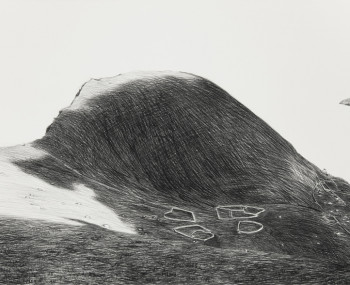

Stac Lì, 2018. Ink on paper. 380 x 570 mm

Memoria Histórica and Orcadians: Seven Impromptus chart well the manner in which I expressed myself pictorially at the time and are bodies of work of which I am extremely proud. Their shared theme is place and the human intervention of it, narrative, time and memory. In terms of the character of my drawing what both do as well, when viewed alongside each other, is represent a journey of progression, exhibiting the development of my visual language. I learned a great deal during each project, not only in terms of the technical process of drawing but also on an emotional level; to be happy, and confident with the way I work. This was not a signal that allowed me to be complacent with my working processes but one that gave me the confidence to accept a point from whence I could expand and move forward creatively.

Memoria Histórica was my first series of drawings to use narrative and the themes of memory, time and place. Although the drawings are tight with detail, all A4 in size, the drawn lines show signs of growing expressiveness and are more confident than in earlier work. The drawings also present a more thoughtful spatial awareness; a steady minimising of contextual surroundings.

Orcadians: Seven Impromptus carried the same themes forward. My growing confidence showed itself in various ways: the dimensions of the picture plane were larger, A1 and A2; the media more varied, with their application more adventurous – ink line and layered wash, painted colour in gouache; graphite pencil and ink pen. The level of detail seen in Memoria Histórica remained but the manner in which it was visualised was more assured and exploratory. I felt more in command of tools and media. The change of scale encouraged greater freedom, more room to move, especially in terms of the potentials with mark-making.

Towards completion of Orcadians: Seven Impromptus thoughts of a new project took hold. It is always an exciting period of work; the research, the feeling of utter absorption of a new subject. I become infatuated, almost to the point of obsession.

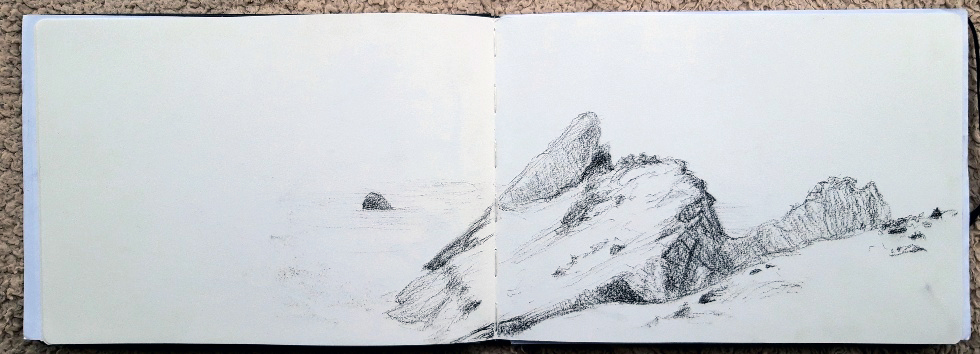

Dùn sketch. Sketchbook, 2019. 210 x 594 mm

Various trips to the Western Isles opened my eyes to dramatic landscapes, to rock and sea; slate quarries on the Isle of Seil, barren moorland on Lewis, the moonscape panoramas of Harris.

As a young man I had a smattering of knowledge about St Kilda, a vague, clichéd feather touch of the facts. It wasn’t until I read Tom Steel’s The Life and Death of St Kilda in the mid 1980s that gaps in my knowledge slowly started to fill. Since then, and with each new book devoured, its story continues to excite my imagination, satisfying my hunger for ever more information.

St Kilda (in Scottish Gaelic: Hiort), is a wild and lonely archipelago 80 kilometres west of the Isle of Harris, is the most westerly of the Scottish Western Isles in the North Atlantic and is made up of four islands, Hirta, Dùn, Soay and Boreray. After many generations of habitation the islands were evacuated – some say cleared – on the 29th August 1930. They are now owned by the National Trust for Scotland and are a dual UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Monuments and memory

Photograph © Simon Manfield

In 2015, while teaching observational drawing at the University of Bradford, my friend and colleague Talya Baldwin and I waited in a café in Leeds for our students to arrive for a session of drawing in the taxidermy department of the city’s museum. We knew our tenure at the university would soon be coming to an end. We mooted ideas of projects for after our departure and came upon a shared interest in St Kilda. Its story captivated both of us.

In August 2017, Talya and I, along with nine others, waited on the pier in Leverburgh, Harris for the two crew members of the boat that would take us across the sea to St Kilda. The previous days’ weather had been storm-force, making a safe crossing look highly unlikely; a text arriving the evening before however had given us the thumbs up. The crossing was rough, challenging for many of the passengers.

A faint silhouette of Borerary and the stacks dropped below the horizon, the swell then raised the boat and land reappeared. With my first sighting of Hirta, the main island of the St Kilda archipelago, what was once a dream now became reality as the boat bashed its way through heavy seas. After two and a half hours we moored in sheltered Village Bay. The island was flooded in warmth and sunlight.

Four and a half hours on shore was not really long enough to fully absorb the poignancy of the place. The main street was empty but full of ghosts; being there summoned memories of faces from old photographs and travelogues. The long sweeping curve of stone dwellings faced the remnants of crofts running down to the bay; the school and kirk, fundamental to village life; the myriad cleits punctuating the landscape; all familiar but now before me, part of my experience.

Boreray and the stacs sketch. Sketchbook, 2019. 210 x 297 mm

We climbed up between Mullach Mòr and Conachair towards the great sea cliffs. At the cliff edge, clusters of fulmars at the tail end of their breeding season were still at their nests. From there we had views to Boreray and the stacks. Then, traversing the landscape to the south-west, we stopped to look down at the village. The heat was unexpected. We could just make out the slow movement of figures making their way back to the pier, so we grudgingly followed.

On the return journey to Leverburgh the boat moved slowly between the island of Boreray, Stac Lì and Stac an Àrmainn. I saw the stacks as monuments and began to envisage how to represent them on paper; dark isolated monoliths emerging from a cavernous sea.

My previous drawing projects were important developmental stages for the St Kilda work: Memoria História enabled me to investigate narrative and memory in pictorial terms. Orcadians allowed that investigation to be explored further. This new project, now titled Monuments and memory, is opening the door wider, giving access to a broader scrutiny of themes such as identity and belonging. The door is now firmly wedged open, inviting in an unstoppable stream of ideas.

I thrive on having a new drawing project and relish the early stages, when I can lose myself in research and devote time to conceptualising a new visual language appropriate to what is in my mind’s eye.

St Kilda had got under my skin, however brief that first visit. I thrive on having a new drawing project and relish the early stages, when I can lose myself in research and devote time to conceptualising a new visual language appropriate to what is in my mind’s eye. I am fortunate that there is already an abundance of visual and literary sources available but am conscious of not wishing to repeat what has already been said.

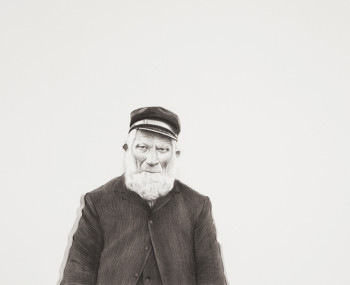

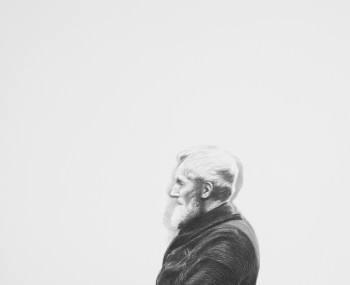

The first drawings rang true with the initial ideas devised at the foot of the stacks. They depict solid structures breaking through the surface of the sea; dark and ancient and geometric in shape. The sea is capricious, though. Its moods are transient, changing form and character with the weather. Perhaps I could leave the sea as a suggestion, its movement and form left to the viewers’ imagination? I focused on details of rock, the rutted surface upon which the St Kildans stood, climbed and hunted, the home for seabirds’ nests and burrows. Rock and seabird: the givers and lifeblood of St Kildan existence. I worked in monochrome with ink, and colour with gouache. Some drawings were quick and some meticulous with every ledge and furrow described with line or tone. In my research St Kildans stared back at me from the pages of old and new publications. They appeared to me to be rooted to the earth, possessing a steadfast authority similar to that of the stacks as they rise from the sea.

The opportunity to return to St Kilda came in August 2019. This time, photographer Sandy Watt joined Talya and I for a longer stay, which enabled a more adventurous and thorough exploration of Hirta. Through the National Trust for Scotland we booked five days’ camping. Early in the week the days were long, still and warm, the midges still very much active. The long daylight hours allowed casual wanderings. There was plenty of time to settle into drawing en plein air. We made longer excursions further afield. We did a day’s walk to the wide sweeping landscape of Gleann Mòr. Just as we reached Cambir at the north-west edge of Hirta, we were caught in a squall while watching the sentinel stacks of Stac Biorach and Sòthaigh Stac standing guard over the neighbouring island of Soay.

My lasting impression of St Kilda is not just of its topographical beauty or a galvanised awareness of the fragility of its seabird colonies, but of the human experience that for generations has impregnated the layers of earth that stretch like skin over the islands’ core.

It has taken time to settle on a definitive theme that offers true attachment, one that continues to develop themes explored in my previous projects. My drawings of the St Kildans as monuments made me wonder: what of their descendants? A direct line can be drawn from them to a house on a street on an island, their names forever linked over generations. Does that trail elicit a compulsion to be custodian of the family genealogy?

The work I have completed is beginning to contextualise the project. But the substance that will fulfil its narrative still needs to be addressed. The finishing flourishes lie with the present, represented by living descendants. If they are willing I hope to make drawn portraits of those I consider the bearers of historical and familial memory, monuments to their past and their future. Yes, they are integral to the visualising of the narrative I am exploring but they are also essential to a more complete telling of the story of St Kilda.