A chance reading …

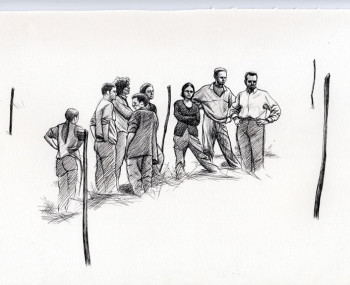

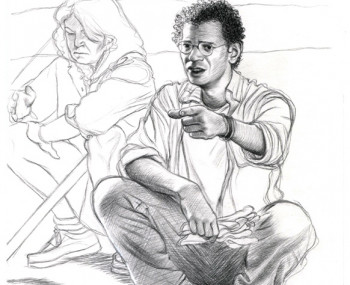

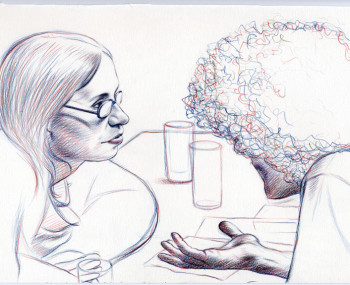

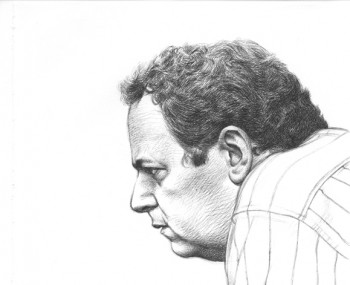

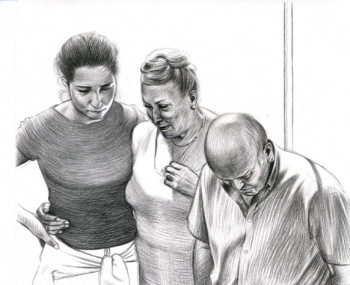

Memoria Histórica in Valdediós

Photograph © Angel de la Rubia

For decades many families in Spain have been clinging to the hope that, one day, the communal grave containing their relatives would be excavated. This would allow them the opportunity to reclaim their family member’s remains and to give them the burial they deserve. Generally, the problem has not been the location of the grave, as this has usually been known. The problem has been that, for many in Spain since the end of the civil war (1936-39), it was, and often still is, easier to forget what occurred than to accept the truth. This denial of historical fact is not the product of ignorance, but the consequence of many decades of fear perpetuated by General Francisco Franco’s long and oppressive regime. Suspicion and the threat of reprisal still exist in Spain, and it is often thought better to look to the future than to accept the past. This way of thinking is slowly changing.

One such excavation was reported by the Guardian’s Giles Tremlett (8/3/03) in an article entitled ‘Spanish Civil War comes back to life’. It described the exhumation of three women who had been assassinated by Franco’s Nationalist troops and the struggle with local authorities to gain permission to rebury them in the local cemetery.

The piece was a revelation. It surprised me that the political divide between left and right, so prevalent during the civil war, was so tangible even today. The division that exists today is fundamental.

The piece was a revelation. It surprised me that the political divide between left and right, so prevalent during the civil war, was so tangible even today. The division that exists today is fundamental. Not only is it polemic but also demonstrably calculated and aggressive. It was only after vigilant campaigning and considerable press coverage that permission was granted for the reburial.

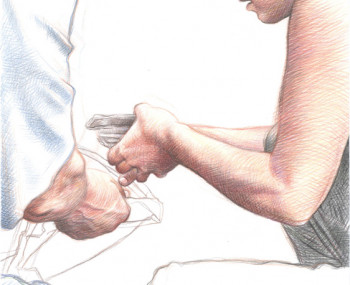

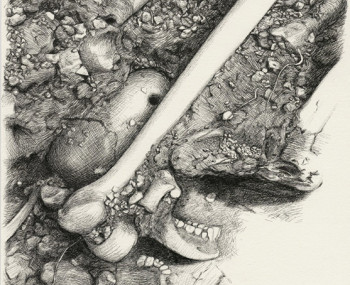

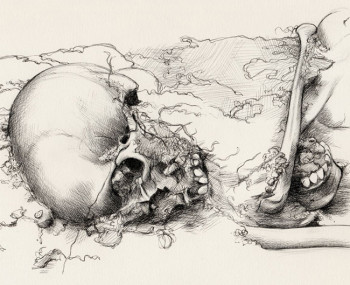

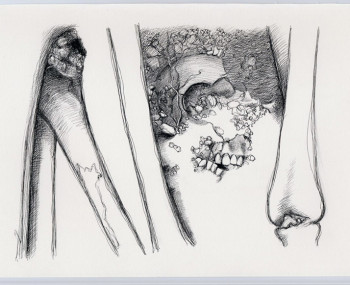

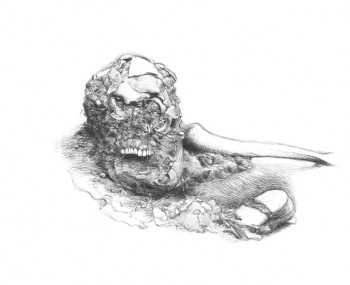

One of the photographs accompanying the article was of a shattered skull, still half buried, its jaw fixed open with the hands of an archaeologist gently sweeping away the surrounding soil. It was a dark and menacing image, but strangely alluring. At the article’s conclusion a call was made for volunteers to take part in further excavations in the summer of 2003.

My reaction was immediate. I felt a profound need to become involved in some way. Spain has, for many years, held a huge fascination for me. I am drawn to the landscape for its diversity and admire the people for their unswerving pride and fortitude. I was willing to volunteer any skills that would be relevant. The most obvious skill I possessed was that of an illustrator.

I submitted my proposal to the International Voluntary Services (IVS) in Leeds who then passed it on to the ARMH. If I were accepted, the project could offer me the opportunity to use illustration as a recording device much as artists and writers had done during the years of the civil war. Most importantly however, perhaps this would enable me to produce a powerful collection of drawings as testament to a significant historical event.

The ARMH accepted my proposal in June 2003.

The excavation took place in Valdediós in the northern province of Asturias and commenced on the 15th July, running for approximately three weeks. The aim was to excavate a communal grave containing the bodies of twenty-nine employees of La Cadellada psychiatric hospital, victims of a mass killing perpetrated by the Navarrese Nationalist regiment, IVth Arapiles Battalion no.7, on the 25th October 1937.

Historical Outline

Personnel, August 1937. Photograph © Constantino Suárez

In January 1937, driven from Oviedo by Franco’s rebel attack, the personnel of La Cadellada psychiatric hospital fled the Asturian capital making their way to the abandoned monastery of San Salvador de Valdediós, a distance of some thirty kilometres. Under the administration of the Republican health service a temporary hospital was to be established in the monastery to treat the shell-shocked and battle-fatigued from the front.

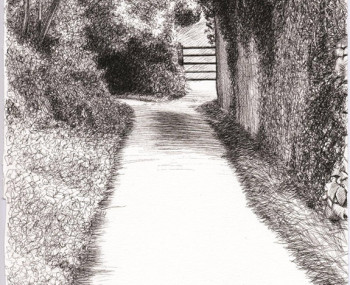

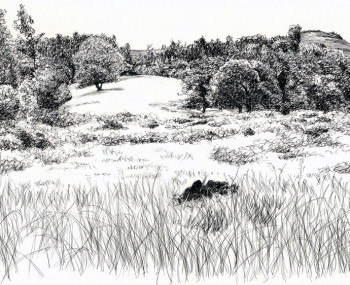

Valdediós is not so much a village as a collection of small hamlets and was, at this point of the civil war, in the Republican zone. It is situated in a beautiful verdant valley, the landscape of which has changed very little since the war: farmlands of grazing milk cows, fields of maize and apple orchards for cider. Idyllic, and for the most part, in early 1937, it was a tranquil and safe setting in spite of the surrounding conflict.

What actually occurred in the days immediately preceding the assassination is unclear. As there is very little written documentation extant, we must look to contradictory testimonies, speculation and rumours as explanation.

The following is the most likely version of events that led to the assassination of personnel in Valdediós.

On the 20th October 1937, the IVth Arapiles Battalion no.7 entered the grounds of the hospital. They immediately singled out five individuals on account of their trade union affiliations, and took them for trial to Gijón. It was later disclosed that two of the individuals were executed.

Five days later, on the evening of the 25th October, the nurses were forced to prepare a celebration with food and dancing for the battalion. According to different testimonies, the soldiers, fuelled by alcohol, raped a number of the female personnel. Later, perhaps to cover up the violation, the soldiers decided to eliminate the victims and any who had witnessed the crime.

Alerted by the din of shouts and screams emanating from the hospital enclosure, a military chaplain appeared. The chaplain would undoubtedly have appeared to the terrified personnel as the possible agent of their salvation but this was not to be the case. He absolved the soldiers of their actions and has alleged to comment, “Do what you must do.”

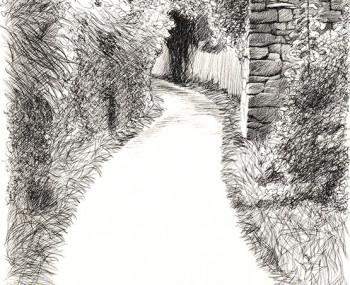

The personnel were then taken from the hospital grounds and marched 200 metres along an adjacent lane to what was then a chestnut wood, now known locally as the Prado de Don Jaime. After being ordered to dig their own graves, the personnel were executed.

The personnel were then taken from the hospital grounds and marched 200 metres along an adjacent lane to what was then a chestnut wood, now known locally as the Prado de Don Jaime. After being ordered to dig their own graves, the personnel were executed. The event was recalled by Bernardo García at the time of the excavation. At the end of that October in 1937 the young García heard shots and screams coming from the Prado de Don Jaime. Days after, he discovered the grave on the hillside meadow: “I only saw the grave for a very short time. After that I ran away as fast as I could. Times were very dangerous”.

It has been claimed that the killings were carried out as an act of retribution. On the morning of the second day of the excavation a large piece of card, tied to the gate at the entrance to the site, bore an anonymous handwritten message. It read: “Cuando termineis aquí buscais las tumbas de las victimas de estos asesinos” (When you have finished here, look for the tombs of the victims of these assassins). At the bottom right hand corner of the placard a syringe was drawn. It is said that the nurses had been gradually killing the patients, who, it has been argued, were not psychiatric patients but wealthy landowners and members of the clergy, with injections of aguarrás (turpentine). Pilar, the monastery guide, confirmed the allegation: “That’s why they were executed! Take a look at the cemetery in the village. The place is littered with their victims!”

Of course the theorising that surrounds the Valdediós killings is not peculiar to that incident. The thousands of mass assassinations carried out during the civil war were performed without trial and those who took part in or witnessed them kept quiet, mostly from fear of reprisal. It is clear that, without official or historical investigation, there will be no definitive explanation for the killings, and now, after many decades, it is unlikely that one will come to light.

The ARMH has estimated that the thirty thousand Spaniards who disappeared or were executed during the years of the civil war and the repression which followed, lie buried somewhere, in mass graves along local roads and lanes, on unused pieces of land or on beaches. Some five thousand bodies are interred in mass graves in the northern province of Asturias, another five thousand surround the city of Granada and almost a thousand lie near Seville, as well as thousands just outside Córdoba.

To date, the remains of more than five thousand have been located at the request of the surviving relatives, and many identified with DNA tests and taken to cemeteries for reburial.

The Excavation

Photograph © Angel de la Rubia

I arrived in Valdediós in the afternoon of the 14th July in the middle of a heavy summer downpour.

The monastery of San Salvador de Valdediós looks across a wide sweep of farmland and is surrounded by hills of towering eucalyptus. In 1992 it became a working Cistercian monastery. Through two black iron gates a footpath passes across an expansive cobbled quadrangle, leading to what would be the volunteers’ makeshift dormitory.

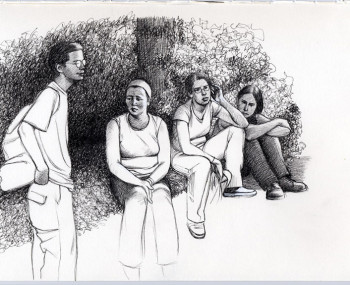

Initially I was to be one of eight volunteers taking part in the excavation. As time passed more arrived, a steady influx of national and international volunteers, then archaeologists, photographers and documentary film crews. It wasn’t until the twenty-eighth volunteer appeared that I realised the importance of this project.

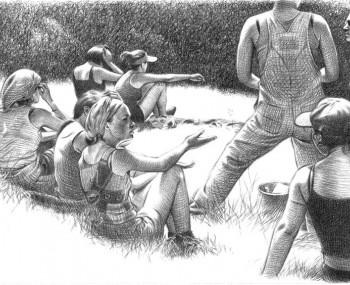

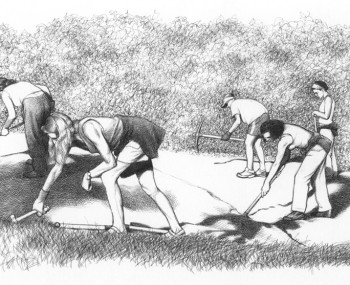

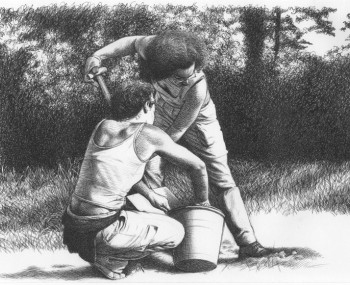

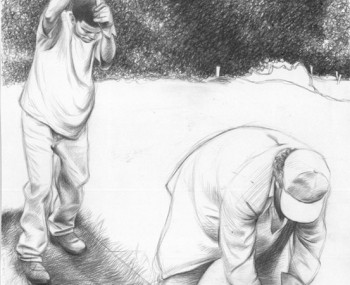

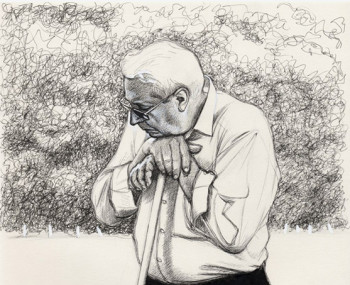

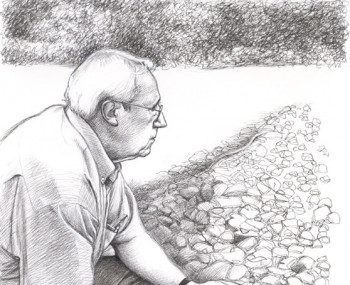

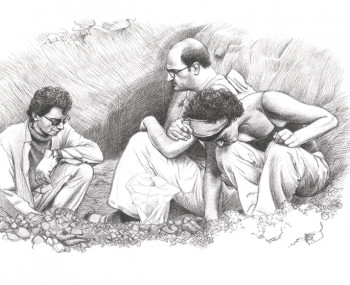

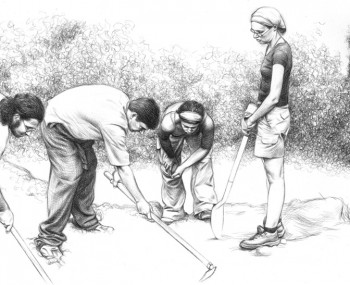

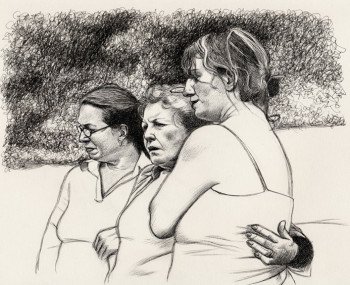

We commenced work on the following day. An area of approximately thirty square metres was staked out in the meadow of Don Jaime. The digging began at the bottom of a steep slope. First cuts into the turf revealed heavy red clay which, with the summer heat, made labour arduous. As the day progressed and the temperature rose, a seemingly endless stream of visitors approached the site. “Visiting this site always makes me shudder,” explained Josefina Nieto, who was only three years old when her mother, one of the nurses, was assassinated. Her father had died shortly before, in 1936, as a Republican soldier at the front. “For a very long time, I thought it would be better not to touch my mother’s grave, with all these other people buried in it. But now, I consider this to be an unworthy resting place for my mother”. Speaking in a low and gentle voice she added: “It would have been so much better if they had started searching for the corpses many, many years ago”.

It appeared to me that, after nearly seven difficult decades, the spirit that had been restrained by an oppressive and authoritarian dictatorship had resurfaced in these people as they broke into the upper crust of the earth.

Each visitor offered advice as to the whereabouts of the grave. Some shared their recollections of Valdediós at the time

of the killings and many attacked the clay with a pick or shovel. It appeared to me that, after nearly seven difficult decades, the spirit that had been restrained by an oppressive and authoritarian dictatorship had resurfaced in these people as they broke into the upper crust of the earth.

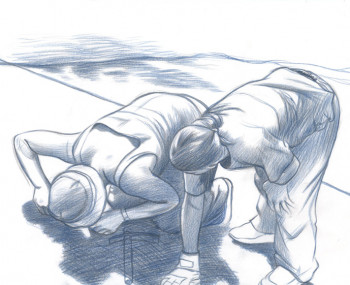

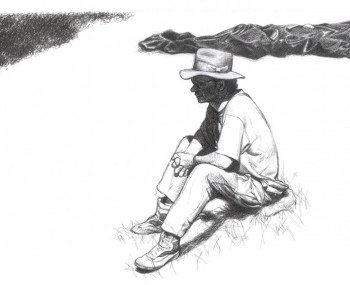

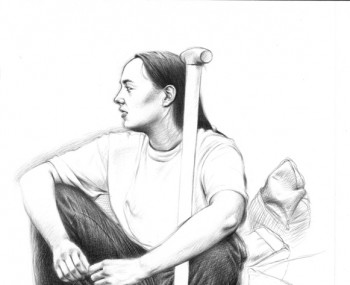

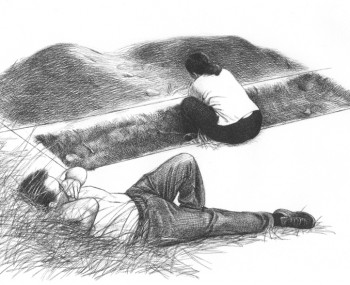

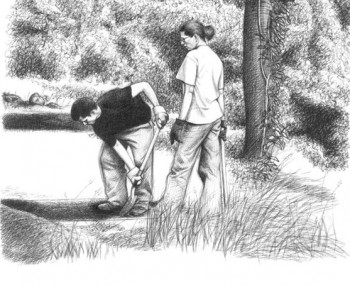

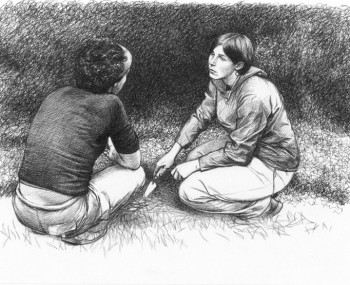

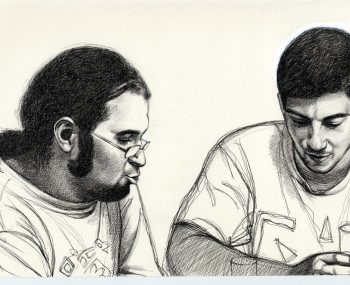

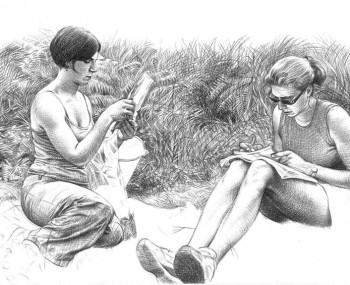

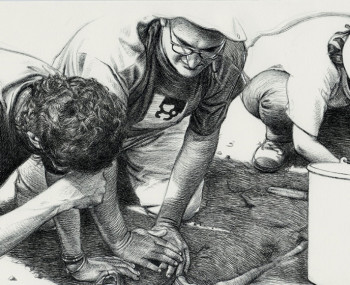

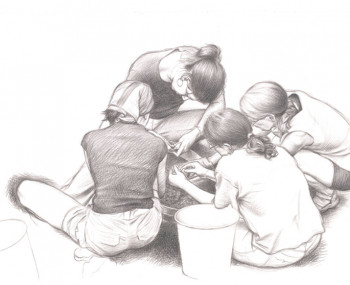

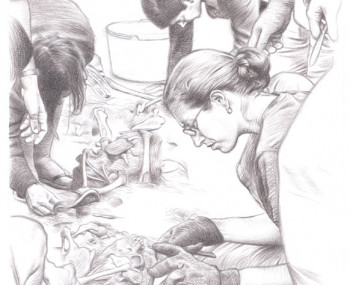

For the first few days I worked on site sketching from life. I made quick sketches in ink or graphite pencil. The shapes and gestures created by figures bending, digging or resting were striking. However, as the day wore on I became aware of missing opportunities elsewhere on site.

The speed in which people worked made drawing from life cumbersome. All manner of reactions and movements occurred at once. Frustratingly, due to this rapidity of action I was unable to capture the various scenes on paper. I began to use my camera, using up roll after roll of film.

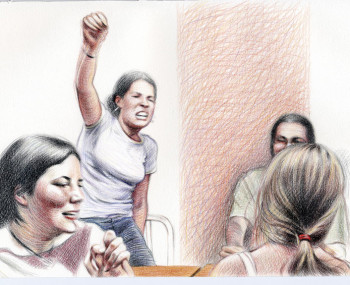

At the beginning of the second week, with no sign of the grave and tempers flaring, the excavation was temporarily halted. An uncomfortable atmosphere of conflict hung palpably in the air. Clandestine meetings were held. Irritation and anger were clearly visible on the faces of the organisers. It all came to a head one evening in the local bar, when it was disclosed that political, and it appears personal, differences within the local branch of the ARMH threatened to end the excavation. The volunteers’ response to this was passionate. The following morning six international volunteers and two team leaders departed.

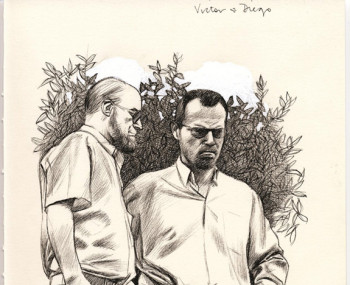

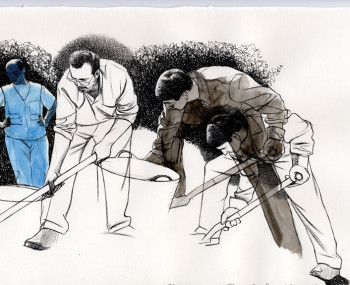

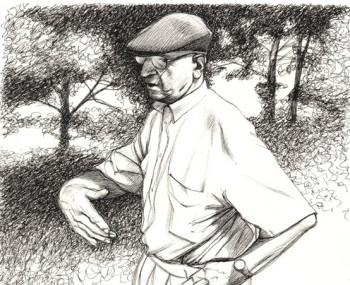

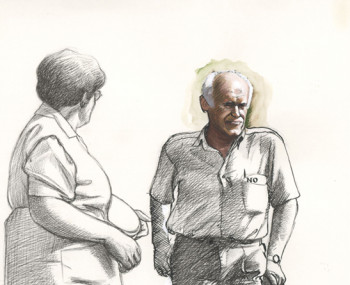

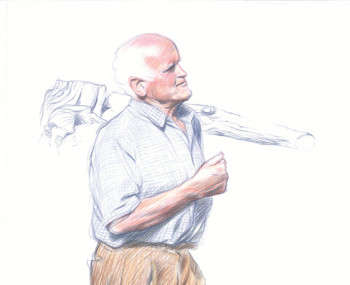

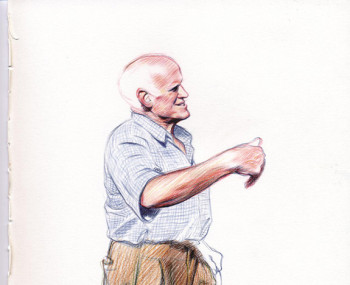

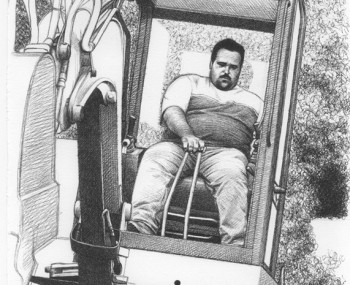

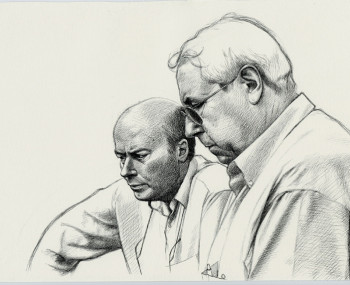

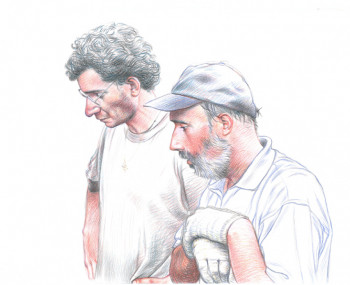

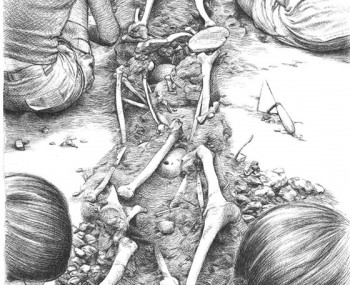

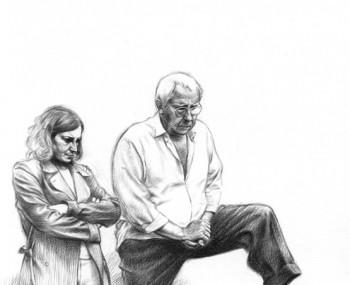

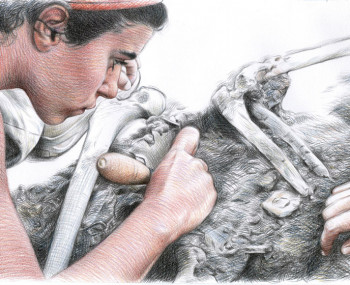

Later that day, after being alerted to the on-going discord within the camp, Emilio Silva, president of the ARMH, arrived to find a way to continue the excavation. He was well aware that the dig was under close scrutiny by the local media and as Valdediós had turned into something of a cause celebre for the association it put immense pressure on its reputation. Emilio Silva is an imposing figure, possessing a calming and cogent demeanour. Along with Silva, and arriving like a whirlwind, Professor of Forensic Medicine Francisco Etxeberria from the University of País Vasco was appointed as leader. An intensely focused professional, Etxeberria, with anthropologist Lourdes Herrasti and the remaining archaeological team recommenced work on site. With the additional help of a mechanical digger, the first of the remains were located on the 24th July.

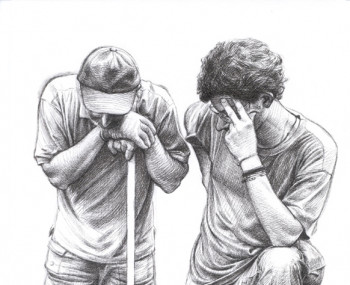

As the digger gouged into the earth, uncovering the first of the victims’ bones I witnessed scenes of extraordinary emotion. Towards the end of the second week the extent of the carnage was exposed in the form of a shallow L-shaped grave. The most shocking aspect was not the elongated form of the grave itself – the realisation that the victims were forced to contrive the awkward shape due to its position in the chestnut wood at the time of the killing was poignant – or the victims’ tangled remains lying as they had fallen, but the emergence of personal effects by their sides. These gave the unrecognisable bodies identity.

Everyone worked or watched in a manner that was focused and respectful. I was surprised by my feelings of impassivity. I did however feel a great sadness for the relatives who witnessed the exhumation. One such relative, Antonio Piedrafita, was called by one of the archaeologists. The shattered skull of his father displayed what would identify him: a row of gold teeth.

Eighteen of a possible twenty-nine bodies were recovered and taken away for DNA testing at the beginning of August.

On a personal level I have difficulty expressing how my involvement in this project has affected me. My participation has enabled me to produce a series of drawings of which I am immensely proud. However, that pride is shallow compared with the emotional effects of a nation coming to terms with a debilitating past. Spain has changed. Decades of latent grief are now unfurling. Beneath the grief lies a new determination.

Text © 2007 Simon Manfield and Rop Zoutberg

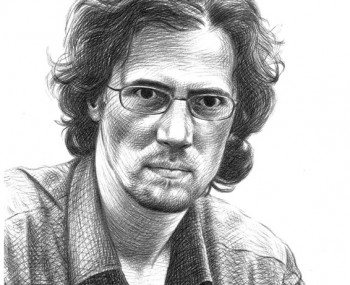

The Memoria Histórica series of drawings were completed towards the end of 2006, three years after the exhumation in Valdediós. The collection comprises sixty A4 drawings in various media on 150 gsm acid free cartridge paper, including pencil, 01 Pilot drawing pen, Berol Karismacolor coloured pencil, Winsor and Newton Designers gouache and Winsor and Newton ink.

In August 2004 twenty drawings from the collection were exhibited at Imperial War Museum North in Salford as part of their Reactions series. Since then Memoria Histórica has been shown at Casa de Cultura, Villiviciosa and Librería Cervantes, Oviedo, Asturias (January – March 2005); an expanded version at ArtsMill, Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire (August 2005); Gallery II, University of Bradford (January 2006); the Eden Project (September 2007) and under the exhibition title Lines of Memory at Glasgow School of Art (October 2010). In March 2014, for the first time, all 60 drawings were exhibited at ArtsMill in Hebden Bridge, West Yorkshire. This show included an edited version of documentary film-maker Rafael del Vigo’s fim The Valley of God.

Articles pertaining to my drawings and experiences in Valdediós have been published in various periodicals including Kommune (German arts/political periodical, December 2003); Association of Illustrators Journal (December/January 2004) and The Drouth (Scottish arts periodical, November 2007).

Drawings from Memoria Histórica have appeared in the 2008 publication Memoria y reconstrucción de la paz – Enfoques Multidisciplinares en Contextos Mundiales, published by the University of Granada and Professor Paul Preston’s The Spanish Holocaust – Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain in March 2012 (HarperCollins).

Please contact me if you are interested in exhibiting Memoria Histórica.